Il senso della pittura

di LUCIANA RAPPO

1999

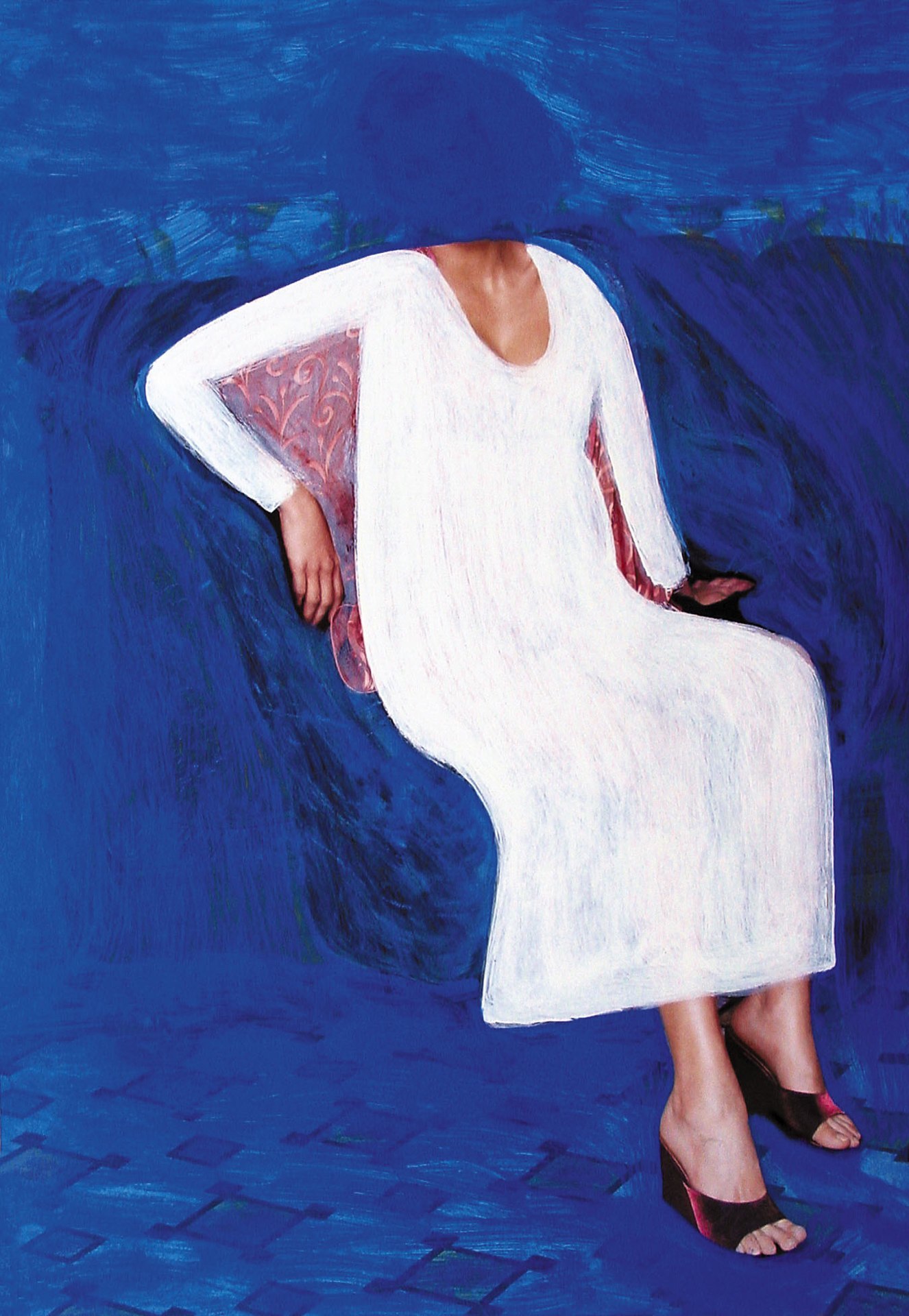

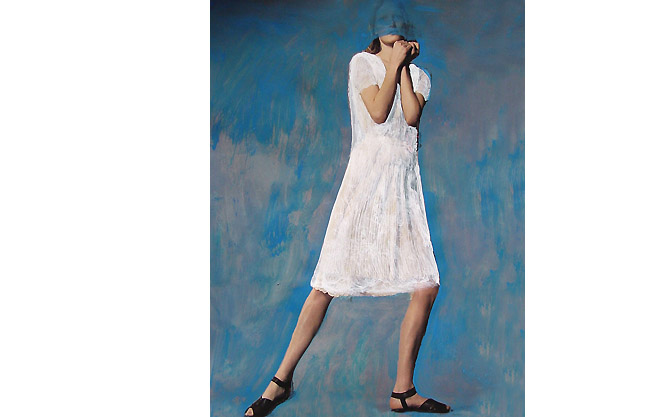

Il blu è denso, magmatico, mistico. La veste bianca: e il colore va a posarsi su una figura, le si spennella addosso, la cancella e la ricrea lasciando affiorare le mani, il collo, i piedi, raramente le labbra, mai uno sguardo. Oppure il rosa, spinto, provocante, poco indulgente ma anche disarmante e ancora questa forma-presenza bianca che cancella un’altra forma-assenza. È un ritratto, un’“istantanea” presa durante la pausa di un viaggio a dorso d’asino, anch’egli affiorante, ma non completamente, dalle pennellate rosa.

Altre volte sono fiori o piccoli alberi a bucare il velo della pittura: essi preesistono sulle stampe di un giornale o di una rivista, fanno parte di un altro mondo, il mondo reale dello scatto fotografico, delle immagini che si sfogliano e, giunte nel luogo del sacrificio, vengono sommerse dalla pittura, si perdono e scompaiono per riapparire dentro un’altra forma e un’altra storia.

La pittura, qui, è un luogo, vi si incontrano presenze e assenze, lo spazio dell’opera è un respiro continuo in cui la figura e lo sfondo, la pennellata e l’immagine seriale ricercano e trovano il loro equilibrio.

Il luogo fisico nello spazio dell’opera è anche il luogo mentale in cui sono calate le figure: sulle tavole su cui viene incollata la carta appaiono dunque frammenti di storie di Maria Vergine e di Angeli, di Avventi e fughe in Egitto, le figure diventano icone e la storia personale una storia collettiva.

Queste figure sono anche tracce di tempo e di tempo passato parlano i colori impiegati per gli sfondi, i blu e i rosa usati come i fondi oro della pittura del ’2-’300; le figure stesse in parte frammentarie, nel loro affiorare alla luce come se fossero state scoperte sotto strati di intonaco, sono ieratiche e geometriche, emanano primitività e purezza al tempo stesso e ricordano i personaggi femminili (la figura è sempre femminile nelle opere di Paracchini) cantati nella lirica provenzale e nei sonetti dei primitivi poeti italiani.

Ma nel contagio tra i linguaggi espressivi, nel modificarsi delle immagini con interventi minimali che seguono un preciso piano intellettuale, nella contemporaneità di presenza-assenza, passato-presente, luogo fisico-luogo mentale, si avverte che qualsiasi rimando a passati culturali è confluito in queste opere e si è trasfigurato.

L’arte, la pittura in questo caso, deve continuamente ricercare un proprio senso, incessantemente messa a confronto con immagini seriali, elettroniche, virtuali, fortissime, che stanno nel profondo del nostro inconscio collettivo come scenari delle nostre emozioni.

Nelle opere di Paracchini l’immagine pittorica s’impone cancellando un’altra immagine; e in questo processo svelando un mondo parallelo, ambiguo ed estremo, colmo di tensioni spirituali e sensuali al tempo stesso.

Il forte carattere concettuale di queste opere si mitiga nell’autoironia, per esempio, dei titoli delle opere; frammenti di canzoni melodiche captati casualmente.

Tutto questo ci emoziona. È successo a me, nell’estate del 1998 vedendo per la prima volta le piccole tavole di Riccardo durante la mostra “Qui, là, ovunque”.

Il mondo parallelo ed “altro” (che ci somiglia) ricreato in queste opere è, forse uno degli aspetti che andiamo cercando quando vorremmo capire che senso ha, oggi, un quadro.

Testo apparso su Juliet n° 94, Ott-Nov 1999.

GOOGLE TRANSLATION

The meaning of painting

Blue is dense, magmatic, mystical. The white dress: and the color settles on a figure, it is brushed on, it erases it and recreates it, allowing the hands, the neck, the feet to emerge, rarely the lips, never a look. Or pink, bold, provocative, not very indulgent but also disarming and again this white form-presence that erases another form-absence. It is a portrait, a “snapshot” taken during a break in a donkey ride, also emerging, but not completely, from the pink brushstrokes.

Other times it is flowers or small trees that pierce the veil of painting: they pre-exist on the prints of a newspaper or a magazine, they are part of another world, the real world of the photograph, of images that are leafed through and, having reached the place of sacrifice, are submerged by the painting, are lost and disappear to reappear within another form and another story.

Painting, here, is a place, presences and absences meet, the space of the work is a continuous breath in which the figure and the background, the brush stroke and the serial image seek and find their balance.

The physical place in the space of the work is also the mental place in which the figures are placed: on the boards on which the paper is glued, therefore, fragments of stories of the Virgin Mary and Angels, of Advents and escapes into Egypt, the figures become icons and the personal story a collective story.

These figures are also traces of time and time gone by, the colors used for the backgrounds speak, the blues and pinks used as the gold backgrounds of the painting of the 13th-14th centuries; the figures themselves, partly fragmentary, in their emergence into the light as if they had been discovered under layers of plaster, are hieratic and geometric, they emanate primitiveness and purity at the same time and recall the female characters (the figure is always feminine in Paracchini’s works) sung in Provençal lyric poetry and in the sonnets of the primitive Italian poets.

But in the contagion between expressive languages, in the modification of images with minimal interventions that follow a precise intellectual plan, in the contemporaneity of presence-absence, past-present, physical place-mental place, one senses that any reference to past cultures has merged into these works and has been transfigured.

Art, painting in this case, must continually search for its own meaning, incessantly compared with serial, electronic, virtual, very strong images, which are in the depths of our collective unconscious as the setting for our emotions.

In Paracchini’s works the pictorial image imposes itself by erasing another image; and in this process revealing a parallel world, ambiguous and extreme, full of spiritual and sensual tensions at the same time.

The strong conceptual character of these works is mitigated in the self-irony, for example, of the titles of the works; fragments of melodic songs captured by chance.

All this excites us. It happened to me, in the summer of 1998, when I saw Riccardo’s small panels for the first time during the exhibition “Qui, là, ovunque”. The parallel and “other” world (that resembles us) recreated in these works is, perhaps, one of the aspects that we look for when we want to understand what meaning a painting has, today.

Altri Testi…