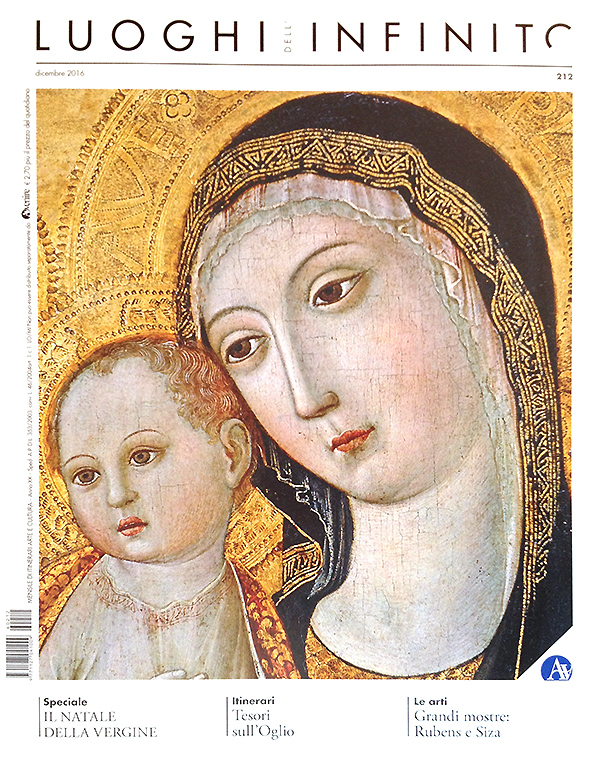

La semplicità dell’impossibile

di PIERANGELO SEQUERI

2016

La scena dell’Annunciazione è stata certamente un tema di speciale affezione per la tradizione iconografica. L’artista, il suo meglio, lo dà come spirito sensibile alla potenza dell’immaginazione che ricrea l’evento.

Non è l’esegesi del testo, né la teologia del mistero, la funzione più alta della sua riflessione creativa (anche se, più spesso di quanto non si creda, l’artista dedito all’impresa di restituire l’enigma del sacro si fa scrupolo di frequentare le giuste letture e i giusti pensieri). Quando questo accade, e lo scavo nella materia espressiva dell’arte è autentico, nella restituzione dell’evento sacro si aprono punti di forza che provocano attenzioni e ripensamenti emozionanti nella stessa lettura esegetica e teologica del testo.

Nei casi migliori, si produce addirittura una circolarità virtuosa: l’immaginazione artistica riapre stimoli vitali nella lettura convenzionale, teologica o devota, del testo; allo stesso modo che la riscoperta di qualche più penetrante esegesi del testo, stimola la vitalità della restituzione artistica a uscire dall’inerzia del manierismo iconico.

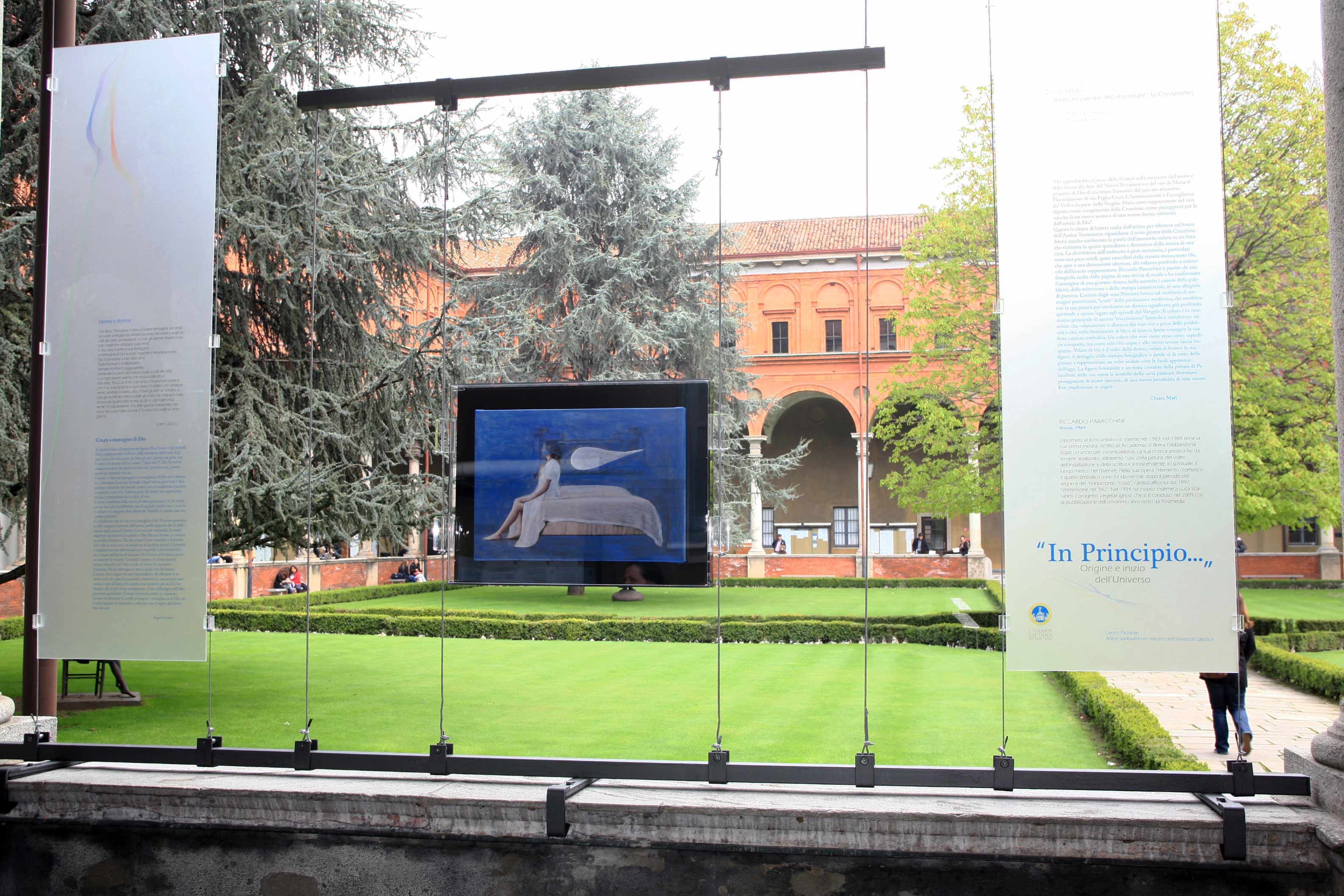

La stanza, il luogo chiuso dell’Annunciazione che simboleggia il grembo dell’incarnazione, che si lascia commutare nel più aperto e ampio ingresso-giardino della casa della nuova creazione e della nostra ammissione all’ospitalità di Dio, aperta alla generazione del Figlio. Il letto stesso, con il suo evidente simbolismo nuziale, che a volte c’è e non c’è allo stesso tempo (Leonardo). E talvolta c’è soltanto quello.

Nella rilettura recente del pittore Riccardo Paracchini (2011) la ragazza è intercettata dall’angelo invisibile (solo le ali si lasciano vedere, ma come fossero ali della Donna) prima che si corichi. Ancora seduta sul letto viene avvolta dal suo passaggio in cui si compie la trasformazione. Insomma, c’è da ragionare anche per teologi ed esegeti. In ogni caso, con frutto per entrambi. L’immaginazione dell’arte forza la simbolicità del dettaglio e oltrepassa la linearità del concetto. Ma porta allo sguardo piegature del testo ed e del senso dell’esperienza di rivelazione che non sono accessibili in altro modo. E che il concetto, da solo, finisce per semplificare o per sciogliere, con secca perdita delle suggestioni stesse offerte dal racconto sacro e dall’esperienza umana dell’evento. Per non perdere di vista il Mistero cristiano, in cui lo Spirito abita le forme e le forze del sensibile umano, in modo che è possibile solo a Dio, è bene che l’arte e la teologia, senza confondere i loro doni spirituali, non si perdano di vista.

Pierangelo Sequeri, teologo e preside del Pontificio Istituto Giovanni Paolo II

testo estratto da “Luoghi dell’infinito” 212, dicembre 2016

GOOGLE TRANSLATION

The simplicity of the impossible

The scene of the Annunciation has certainly been a theme of special affection for the iconographic tradition. The artist, at his best, gives it as a spirit sensitive to the power of the imagination that recreates the event.

It is not the exegesis of the text, nor the theology of the mystery, the highest function of his creative reflection (even if, more often than one might think, the artist dedicated to the enterprise of restoring the enigma of the sacred is scrupulous about frequenting the right readings and the right thoughts). When this happens, and the excavation into the expressive material of art is authentic, in the restitution of the sacred event strong points open up that provoke attention and emotional rethinking in the same exegetical and theological reading of the text.

In the best cases, a virtuous circularity is even produced: the artistic imagination reopens vital stimuli in the conventional, theological or devout reading of the text; in the same way that the rediscovery of some more penetrating exegesis of the text stimulates the vitality of artistic restitution to emerge from the inertia of iconic mannerism.

The room, the closed place of the Annunciation that symbolizes the womb of the incarnation, which allows itself to be converted into the most open and spacious entrance-garden of the house of the new creation and of our admission to God’s hospitality, open to the generation of the Son. The bed itself, with its evident nuptial symbolism, which sometimes is there and is not there at the same time (Leonardo). And sometimes there is only that.

In the recent reinterpretation by the painter Riccardo Paracchini (2011) the girl is intercepted by the invisible angel (only the wings can be seen, but as if they were the Woman’s wings) before she goes to bed. Still sitting on the bed, she is enveloped by his passage in which the transformation takes place. In short, there is reason to be had also by theologians and exegetes. In any case, with fruit for both.

The imagination of art forces the symbolism of detail and goes beyond the linearity of the concept. But it brings to the gaze folds of the text and of the sense of the experience of revelation that are not accessible in any other way. And that the concept, by itself, ends up simplifying or dissolving, with a clear loss of the very suggestions offered by the sacred story and by the human experience of the event. In order not to lose sight of the Christian Mystery, in which the Spirit inhabits the forms and forces of the human sense, in a way that is possible only to God, it is good that art and theology, without confusing their spiritual gifts, do not lose sight of each other.

ANNOTAZIONE

In una mail monsignor Pierangelo Sequeri scrive:

Il lavoro mi ha colpito molto, soprattutto per la straordinaria e originale risoluzione in termini di “materia pittorica” – non didascalica, non intellettualistica, ma neppure semplicemente emozionale e retorica – delle molte componenti simboliche di un tema così denso come quello di Annunciazione Incarnazione.

Altri Testi…