Presenza, aria, presentimento

di ELENA DI RADDO

2002

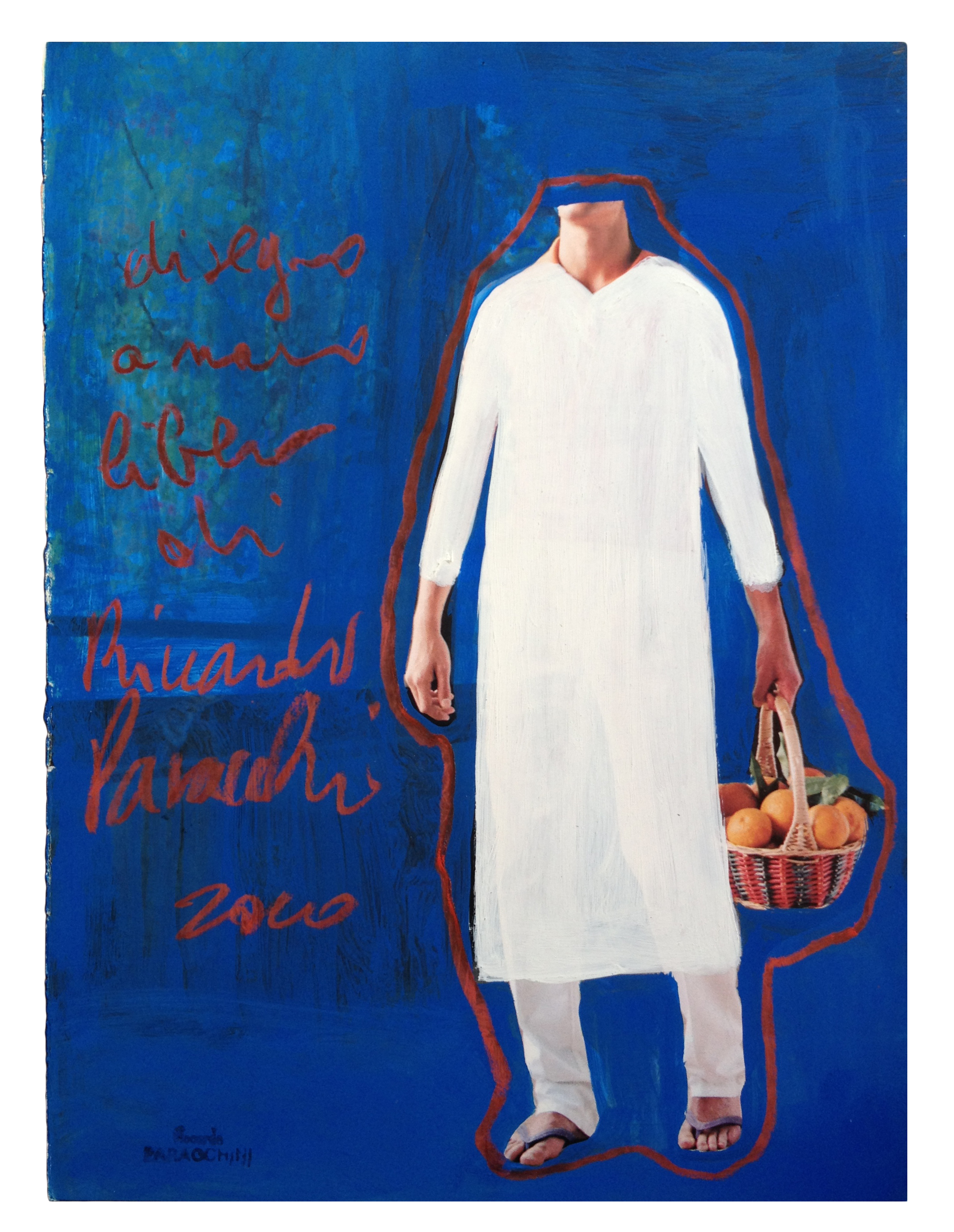

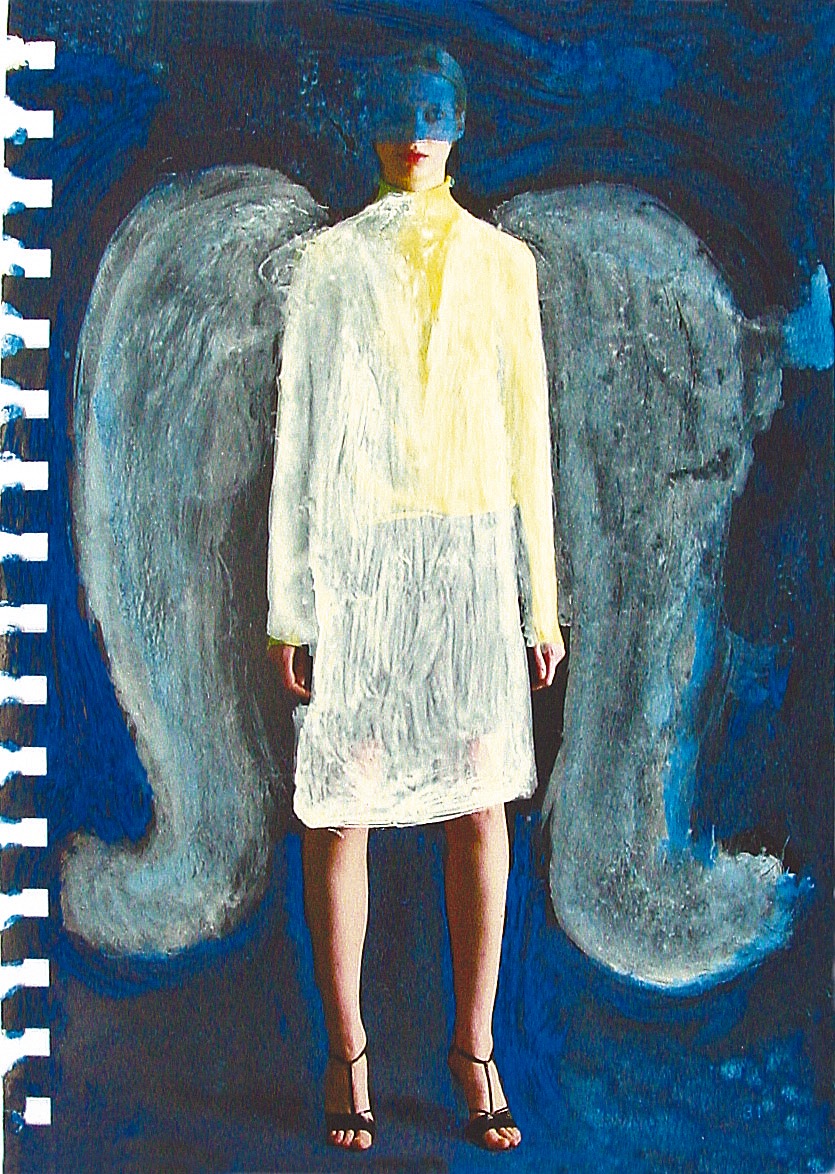

La favola di Butades pone all’origine della pittura anche un altro aspetto della realtà umana, l’amore, che ha portato alla necessità di tramandare alla memoria i lineamenti dell’amato. All’amore fa riferimento il lavoro di Riccardo Paracchini che si ‘innamora’ sempre delle donne di carta, ritagliate dai giornali illustrati, che sceglie come punto di partenza dei suoi dipinti. In Paracchini l’errore ha un valore morale, e la pittura una funzione educatrice. L’artista sceglie accuratamente le fotografie di giovani donne pubblicate sulle riviste di moda e procede con la pittura a coprire parti del loro corpo, a vestirle di colore blu con il quale nasconde anche il loro volto. Le donne si trasformano in questo modo in creature angeliche con le ali, o in Madonne, assumono una valenza universale. La pittura procede dal contingente all’eterno, idealizza il sentimento d’amore.

Nonostante l’impostazione materialista della società dei consumi, le cose del mondo non sono semplici presenze mute. Il loro stesso mutismo ci induce a sprofondare nel ricordo dell’uso che ne facevamo o del bisogno che ne abbiamo. In un suo libricino Nabokov sostiene che non bisogna lasciarsi trasportare dal ricordo dell’oggetto che non può portare che nostalgia e rimpianto. Le cose sono, nel momento stesso in cui esistono. La loro storia ci porterebbe troppo lontano nel tempo, annullando il loro essere presente, temporaneo, immanente. Rimanere in bilico tra presente e passato significa riuscire a superare la trasparenza degli oggetti, la permeabilità del presente. Pensare alle cose, ad esseri inanimati, privi di sentire, di organicità, di un loro tempo interiore, significa spostare l’attenzione su ciò che sta al loro esterno, sulle relazioni che intrattengono con noi. La storia apparente di una cosa diviene così la nostra storia, con i sentimenti, le riflessioni, le emozioni che li hanno resi protagonisti di certi eventi.

Il tempo degli oggetti è il nostro tempo, il loro spazio è lo spazio della nostra interazione. Nel momento stesso in cui pensiamo un oggetto, esso non esiste più per se stesso, ma assume i caratteri del nostro essere e del nostro pensiero. Le cose appartengono alla nostra quotidianità più delle vicende del mondo. Anche l’assoluto cui sembra alludere la pittura di Paracchini è implicato con la contingenza: nell’aspirazione alla moralità del suo lavoro è possibile leggere una componente tutta umana. Le sue pitture sono icone laiche che racchiudono il bisogno dell’uomo di andare oltre la contingenza delle cose. “Cerchiamo l’assoluto – scriveva Novalis – ma ci aspettano soltanto le cose”. In questo paradosso è forse racchiuso un nuovo umanesimo.

Tratto dall’omonimo catalogo “Presenza, aria, presentimento”, 2002.

GOOGLE TRANSLATION

Presence, air, premonition

Butades’s fable also places another aspect of human reality at the origin of painting, love, which has led to the need to pass down to memory the features of the beloved. The work of Riccardo Paracchini refers to love, who always ‘falls in love’ with paper women, cut out from illustrated magazines, which he chooses as the starting point for his paintings. In Paracchini, error has a moral value, and painting an educational function. The artist carefully chooses photographs of young women published in fashion magazines and proceeds with painting to cover parts of their bodies, to dress them in blue which also hides their faces. In this way, women are transformed into angelic creatures with wings, or into Madonnas, they take on a universal value. Painting proceeds from the contingent to the eternal, idealizes the feeling of love. Despite the materialistic approach of consumer society, the things of the world are not simple mute presences. Their very silence leads us to sink into the memory of the use we made of them or the need we have for them.

In one of his little books, Nabokov argues that we must not let ourselves be carried away by the memory of the object that can only bring nostalgia and regret. Things are, in the very moment in which they exist. Their history would take us too far back in time, canceling their being present, temporary, immanent.

Remaining balanced between present and past means being able to overcome the transparency of objects, the permeability of the present. Thinking about things, inanimate beings, devoid of feeling, of organicity, of their own internal time, means shifting our attention to what is outside them, to the relationships they have with us. The apparent history of a thing thus becomes our history, with the feelings, reflections, emotions that have made them protagonists of certain events.

The time of objects is our time, their space is the space of our interaction. The very moment we think of an object, it no longer exists in itself, but takes on the characteristics of our being and our thoughts. Things belong to our daily life more than the events of the world.

Even the absolute to which Paracchini’s painting seems to allude is implicated with contingency: in the aspiration to morality of his work it is possible to read a completely human component. His paintings are secular icons that enclose man’s need to go beyond the contingency of things. “We seek the absolute – wrote Novalis – but only things await us”. Perhaps a new humanism is contained in this paradox.

Altri Testi…